A groundbreaking cancer vaccine for dogs, heralded as “truly revolutionary” by experts, is making significant strides in clinical trials that commenced in 2016. This vaccine, aimed at improving cancer treatment in canines, might also have implications for human cancer therapies. Over 300 dogs have received this vaccine so far, with survival rates for dogs with certain types of cancer increasing from approximately 35 percent to 60 percent within twelve months. A noticeable reduction in tumor size has been observed in many cases.

The vaccine, known as the Canine EGFR/HER2 Peptide Cancer Immunotherapeutic, originated from research into autoimmune diseases. Autoimmune diseases occur when the immune system mistakenly attacks the body’s tissues. This vaccine aims to redirect the immune system’s focus towards combating cancer cells. “Tumors, in many respects, resemble autoimmune disease targets,” explained Mark Mamula, a rheumatologist at Yale University’s School of Medicine. He elaborated, “Cancer cells originate from your own tissue and are targeted by the immune system. However, in this instance, we desire the immune system to attack the tumor.”

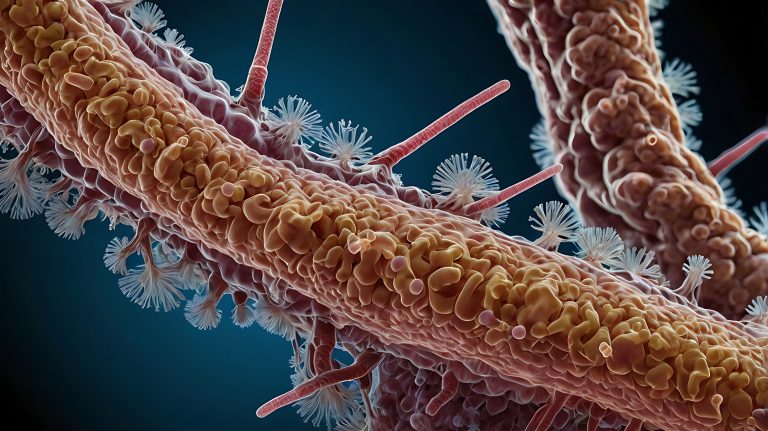

This innovative treatment prompts immune cells to produce antibodies that attach to tumors, disrupting their growth. These antibodies target the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) and human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2). Mutations in these proteins can lead to uncontrolled cell division in certain cancers affecting humans and dogs. Unlike existing treatments that rely on a single type of antibody, this vaccine induces a polyclonal response, utilizing antibodies from various immune cells. This approach significantly reduces the cancer’s ability to develop resistance to the treatment.

Gerry Post, a veterinary oncologist at Yale School of Medicine, expressed his excitement about the vaccine’s potential, stating, “In veterinary oncology, our toolbox is considerably smaller than human oncology. This vaccine is indeed revolutionary.”

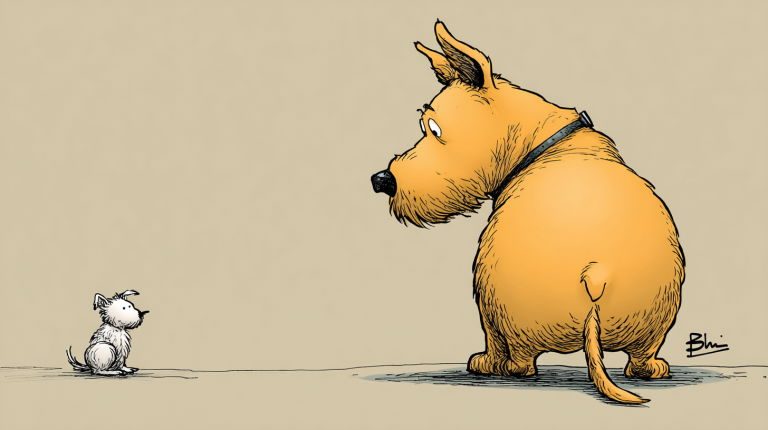

Although currently utilized as a treatment post-diagnosis rather than a preventive measure, the vaccine has already yielded positive outcomes for dogs like Hunter, who overcame osteosarcoma, a bone cancer, and has been cancer-free for two years post-diagnosis. Given that roughly one in four dogs will experience cancer at some point in their lives, the impact of this vaccine could be substantial.

The similarities between canine and human cancers, including genetic mutations, tumor behaviors, and responses to treatment, suggest that this vaccine could also enhance our understanding of human cancers. Despite the challenges in predicting which dogs will respond to treatment, the advancements in canine cancer therapies, including immunotherapies for melanoma and lymphoma, are promising.

“Dogs, like humans, develop cancer spontaneously,” Mamula noted, highlighting the similarities in cancer progression and mutation between dogs and humans. He added, “If we can provide some benefit, some relief, and a pain-free life, that would be the best possible outcome.”

This significant research was detailed in a publication in Translational Oncology.